Paragon Prognosis: Don’t Act Surprised

Paragon Prognosis: Don’t Act Surprised

Imagine this: One day, you find yourself in a bad car accident that requires emergency surgery. The ambulance takes you to an in-network hospital where the operating surgeon is also in-network, but the anesthesiologist on call is not. Good news though – the No Surprises Act (NSA) means that you don’t have to pay more than you normally would if the anesthesiologist was in-network. The bad news: It’s likely increasing premiums. How did this happen? Let’s explore.

First, a bit of background. Back when Congress passed the NSA, there was agreement on the basic principle – insured patients shouldn’t have to pay more when they aren’t given a choice of an in-network provider while receiving care at an in-network facility or in an emergency. However, there was little agreement on how the payer and provider should settle the patient bill. Providers didn’t want to accept the in-network rate without regular access to beneficiary populations (the carrot for being in-network). On the other side, insurers didn’t want to cover the entire out-of-network rate that was designed with higher cost-sharing to encourage beneficiaries to choose the cheaper in-network providers.

To mediate between the parties, Congress included an independent dispute resolution (IDR) process in the NSA. This IDR was based on baseball-style arbitration, whereby two parties come before an independent arbiter (chosen mutually by the parties or, failing that, by the federal government from an approved list) and each submits an offer. The arbiter evaluates them and chooses one. Crucially, the arbiter is not empowered to meet in the middle, which might happen normally with contract negotiations. Congress included some guidelines about which option the arbiter should choose, including the qualifying payment amount (QPA, a payer-specific median of network rates), prior contracted rates between the payer and provider, and level of patient care involved, among other things. Federal agencies issued rules about how to weigh each factor (with emphasis on the QPA being the primary component). Unhappy with too much weight on the QPA, providers sued and the rules became tied up in court.

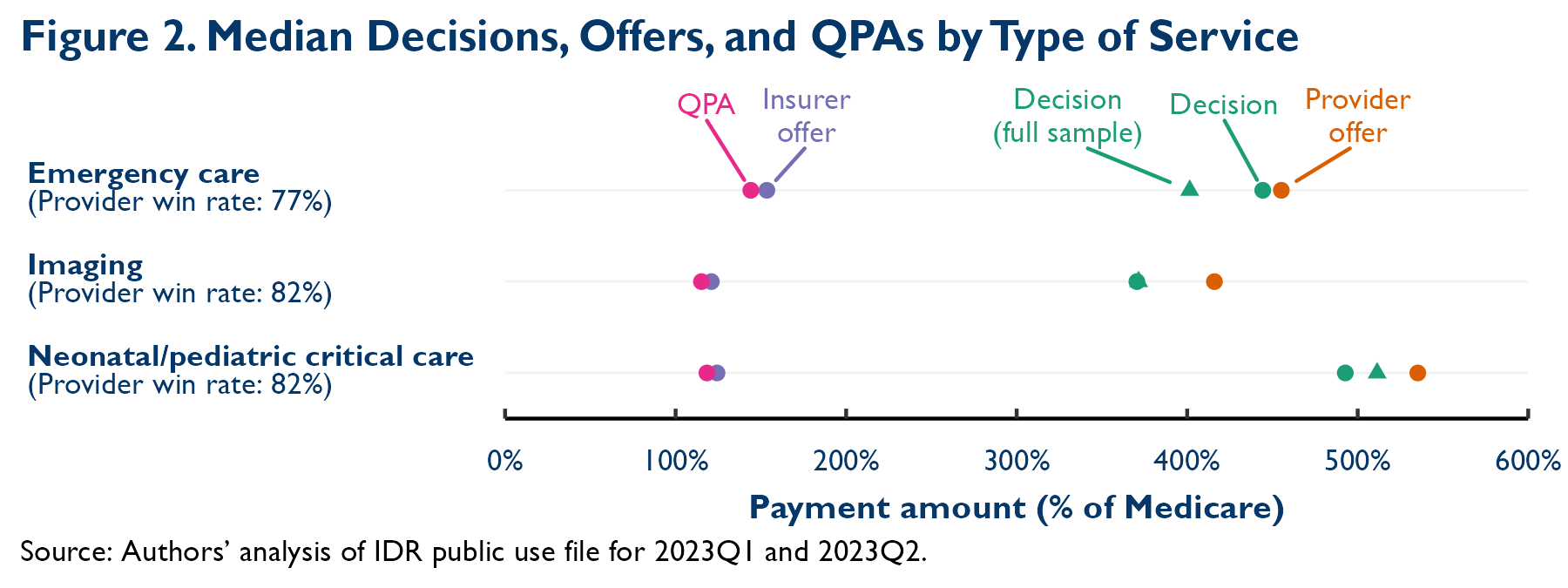

As recent data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) show, the amount of government arbitration has been significantly more frequent than expected and has favored providers (see Figure 1 from my colleagues at Paragon Health Institute and Figure 2 from the Brookings Institution). A Government Accountability Office (GAO) report in December of 2023 stated that HHS, Labor, and Treasury expected about 22,000 disputes in 2022, but between April 15, 2022-July 1, 2023, they received over 489,000. To drive the point home: In the first year of the IDR program, more than 14 times the expected number of disputes were submitted. Due to the large number of disputes and the small number of arbiters, between January 1-June 30 of 2023, only 83,868 payment determinations were made. Approximately 77 percent were in favor of medical providers, facilities, and air ambulance providers.

Figure 1

Why should the average person care about this? First, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) predicted that payments would be close to in-network rates, would thus avoid premium increases, and would reduce federal deficits (through lower Affordable Care Act exchange subsidies and higher taxable wages from lower employer-sponsored insurance premiums). This favorable analysis paved the way for the NSA’s passage. Now, given that IDR payments are significantly higher than expected, we can also expect premiums, and likely federal deficits, to rise.

Second, part of the appeal of the NSA was that it would incentivize providers to be in-network (in essence, reducing their out-of-network payment leverage by prohibiting balance billing on out-of-network charges), making care cheaper for patients and insurers. As the Brookings analysis points out, the higher payments from IDR will likely discourage providers from joining insurance networks, meaning premiums are less likely to decline than originally assumed.

Third, the biggest providers are getting the most increased payments: Brookings notes that “74 percent of services analyzed in this study were tied to physicians affiliated with four large firms”. This jives with CMS’ findings that the top three initiating parties “accounted for approximately 58 percent of all disputes submitted in the first six months of 2023.” This could incentivize providers to join major provider organizations and health systems, increasing concentration and thus prices. More to the point, it’s a clear example of a few companies gaming federal regulations to their benefit and to the detriment of American families.

A huge selling point of the NSA was that patients would pay less without premiums going up. But the best laid plans of mice and men often go awry. Rather than let two private parties figure out how they’re going to resolve the out-of-network price, Congress installed a single-judgement arbitration system with no room for back-and-forth or meeting in the middle. Now, what Americans pay for health care will likely increase.

To fix this, Congress should toss the IDR system and keep government out of private payment negotiations. Put another way, let’s protect patients from surprise payments and let providers and insurers figure out the rest.

Related Content

Subscribe

Sign up now for your health policy updates.